This offseason we’ll be breaking down the performance of each unit – passing and rushing offense and defense – with a look ahead to 2021 and what this means for the Irish. First up is the Notre Dame run game, which brings back a loaded running back room but is working through a complete overhaul of the offensive line. What went well to create an efficient and physical attack in 2020, and what’s the ceiling for this coming fall?

Foreward: Remember, 2020 was an anomaly

In the analysis of the 2020 season, it’s important to remember a few pieces of context. First, Notre Dame played one of the most demanding schedules in FBS. The ACC slate aside from North Carolina may have disappointed, but playing Clemson twice and then Alabama in the faux Rose Bowl will knock down any teams’ average statistics.

Brian Fremeau’s FEI Ratings include a neat strength of schedule rating that projects how many losses an elite team (two standard deviations better than average), good team (one standard deviation better), or average team would lose against those opponents. Playing Notre Dame’s schedule, an elite team projected to lose 2.01 games, 2nd most in FBS behind only Iowa State. It’s easy to envision a typical year without a conference championship game where the Irish would only have played one elite team (there could be zero on the schedule in 2021).

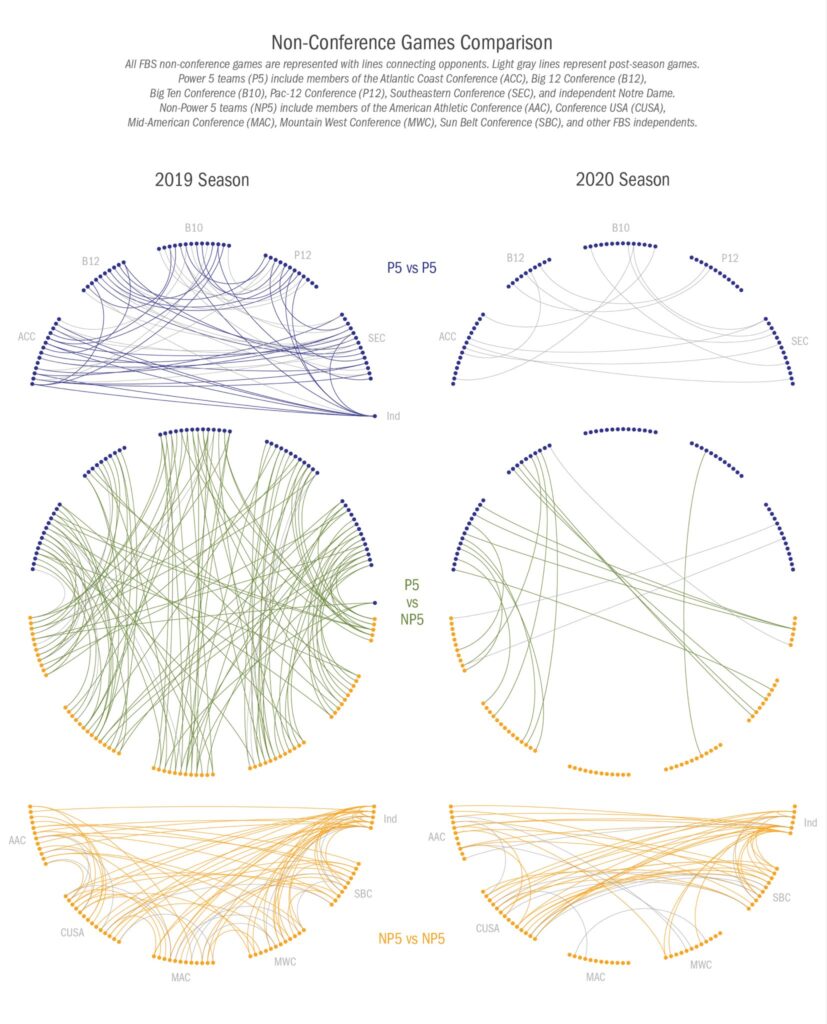

The other significant variable is the overall weirdness of 2020 in a pandemic. Usually, looking at national rankings that are not opponent-adjusted is fairly safe, especially for power five programs that have played a minimum number of quality opponents. Of course, that doesn’t mean there still isn’t variation, but we can mentally adjust with what we know of the relative strengths of the teams and conferences.

With virtually zero non-conference games in 2020 and many programs playing bare-bones schedules, especially the Pac-12 and Big Ten, there’s a lot more noise throughout the data. Advanced stats systems like FEI, SP+, and FPI have a much harder time making opponent adjustments with smaller sample sizes and less connectivity between data sets. As the chart above illustrates (again, credit to Brian Fremeau or the awesome visual), the difference between the pandemic year and a regular schedule is stark with so little crossover. More than any past year, there are legitimate reasons to be skeptical about the reliability of 2020’s predictive value.

The final factor for the upcoming season and projections is the unprecedented amount of returning production across FBS. With the 2020 season not counting toward eligibility and the 85-man scholarship limit relaxed through 2021, many teams have greater returning depth than ever before. Using Bill Connelly’s weighted returning production numbers, the average team brings back 75.8% this season compared to an average of 62.6% over the previous six years. Notre Dame ranks 123rd with just 53% of last season’s weighted production coming back.

Rushing Efficiency

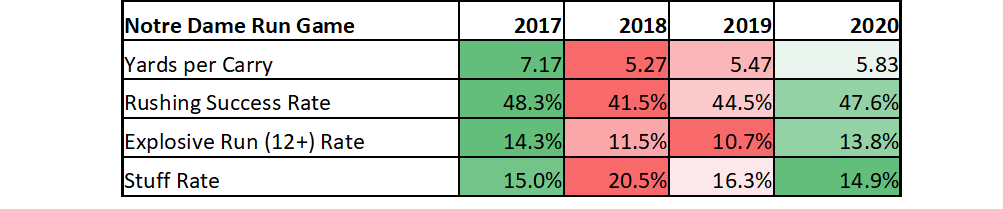

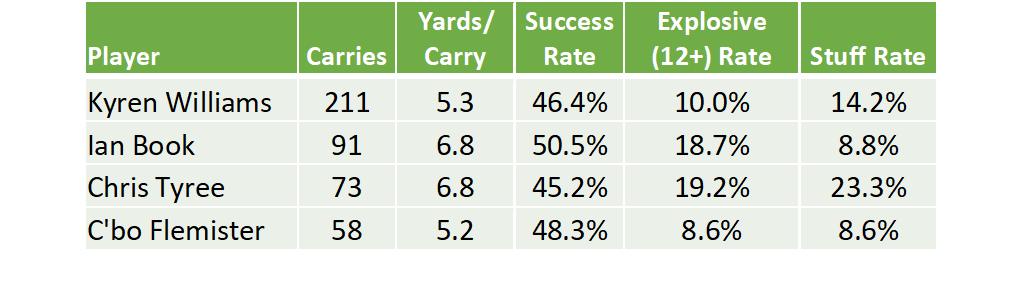

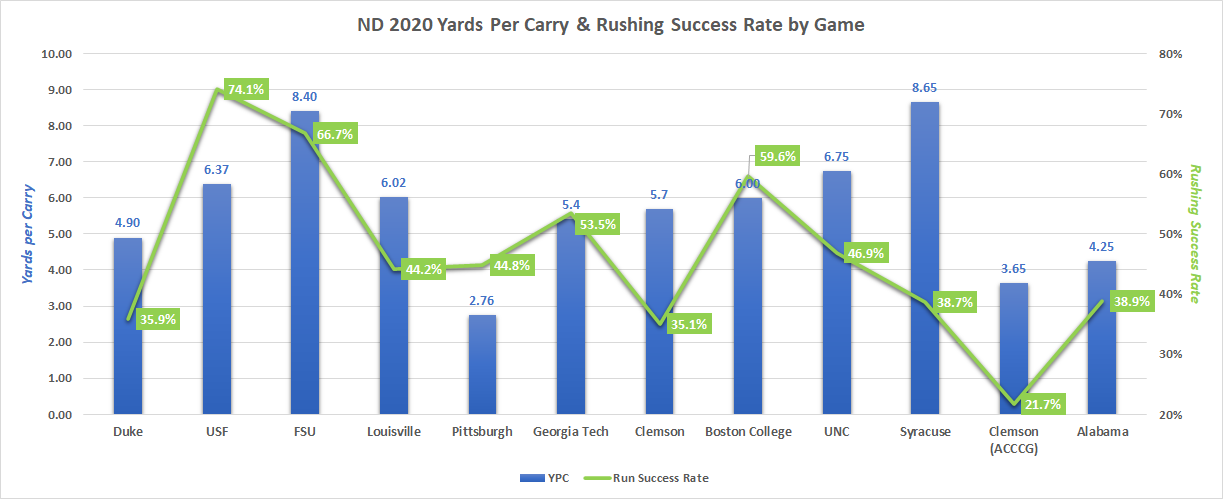

Let’s start with positives – the Irish running attack was incredibly efficient and physically dominated inferior talent. Despite playing three games against playoff-caliber defenses, Notre Dame finished 15th nationally in rushing success rate. The emergence of Kyren Williams combined with an experienced and talented line, Tommy Tremble’s insatiable appetite for putting guys into the ground, and a strong blocking receiving group formed a strong backbone for the offense.

There were few deficiencies to nitpick in the regular season – things started slowly on the ground in the opener against Duke, but by Florida State, the offensive line was mauling defenses. At Pitt, the only poor performance came as Pat Narduzzi and the Panthers were hyper-aggressive against the run; Tommy Rees and Ian Book happily shredded their defense for 9.5 yards per attempt instead. In the first Clemson matchup, it was a grind to rush efficiently, but the long Williams touchdown to open the game and gritty red zone running to close the game were essential for the upset.

The fundamentals behind Notre Dame’s rushing success were extremely healthy. The Irish avoided costly negative runs, finishing 15th in stuff rate allowed (rushes for a loss or no gain). In power run scenarios – 3rd and 4th down with two yards to gain or less – ND converted 78% of the time (32nd in FBS), a dramatic improvement from 62% in 2019 (106th).

The only issues arose when the Irish faced top opponents. A healthy Clemson and Alabama could match the talent in the trenches and could commit to stopping the run with little fear of exposure downfield. Unfortunately, Tommy Rees’ offense tailored to the strengths of his personnel ran out of answers in a couple of these matchups, although the run game was decently effective still against the Tide despite the loss of Tremble in the first half.

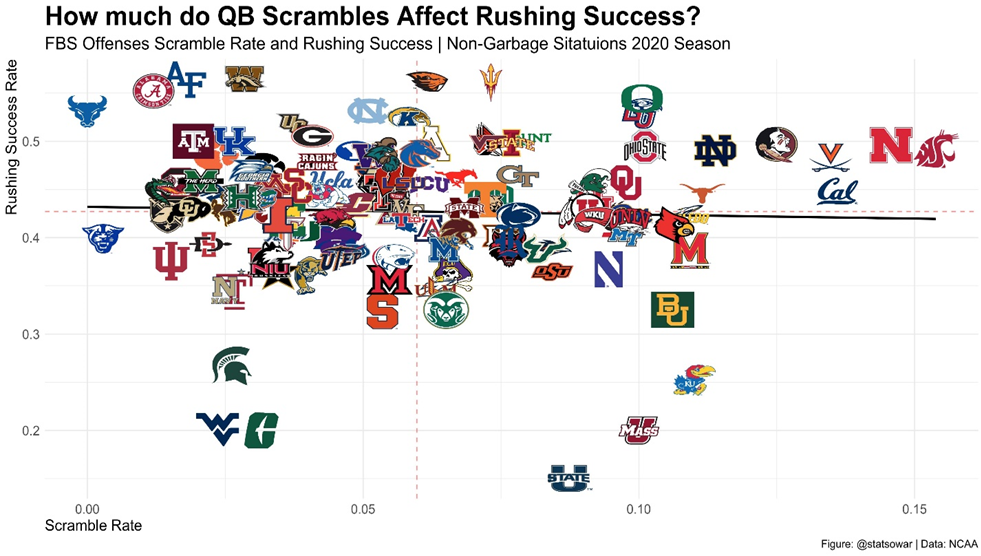

Rushing Explosiveness

Notre Dame ended 2020 ranked 27th in percentage of runs gaining 10+ yards (16.4%), and 40th in 20+ yards (4.6%). Strong but not elite performance generating these home runs isn’t inherently an issue – the Irish ranked ahead of Clemson, Alabama, and Oklahoma in these rates of explosive runs. They also don’t account for opponent adjustments, with the treat of seeing Brent Venables twice and then Nick Saban finally with a healthy defense. But when the rushing game is the backbone of the offense, as it was in 2020, efficiency alone isn’t enough. It requires explosiveness at Ohio State or UNC levels seen above – a tall order.

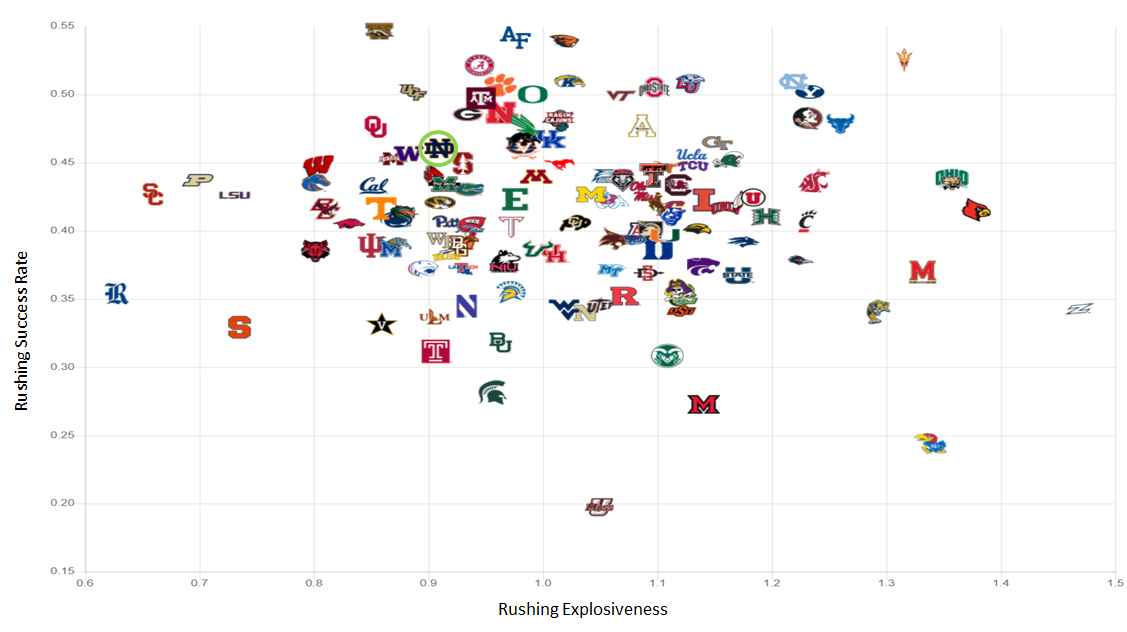

It’s fascinating looking at individual rushing numbers to see how significant Ian Book’s contribution was to run explosiveness. Of course, the numbers are slightly biased towards QBs – with advanced stats, an effective scramble counts as a successful run, but an attempt to scramble out of pressure that’s unsuccessful is logged as a sack and pass failure. Still, Book was Notre Dame’s most efficient runner and neck and neck with Chris Tyree in creating long runs.

The threat of Book’s legs will be sorely missed next season, both designed and improvising. Book scrambled more often than all but five FBS quarterbacks and was extremely successful in those runs. By ESPN’s QBR, Book’s overall rushing contribution was the 10th most of any FBS QB last season, trailing only limited passers like Malik Cunningham, Jordan Travis, Max Duggan, and Adrian Martinez if focused solely on the P5.

Next year the passing offense has the chance to provide more significant support as well. Irish opponents last season weren’t overly concerned with vertical receiving threats, and the high use of 12 personnel allowed defenses to commit many defenders in the box without getting overly exposed. NFL analysis has shown that an extreme amount of rushing success at the top level is predicted by the number of defenders in the box.

In the more heterogeneous college football world, with wider talent disparities and more diverse schemes, the effect may not be quite as strong. But at the top of the sport, it seems reasonable the same may apply, and an offense that can take advantage of what the defense is showing and stay as dangerous with more wide receivers on the field will be key. The Irish can strongly influence the number of defenders in the box through their offensive personnel – more wide receivers on the field at once will keep fewer defenders in – and making defenses harshly feel the consequences of leaving their back end more exposed. Jack Coan isn’t Trevor Lawrence, but if Tommy Rees can instill some of his expertise in reading defenses and audibling into the right run/pass scenarios, that could be a hidden benefit to the run game overall.

2021 Outlook

In a vacuum, it’s hard to envision an improvement in the quality of Notre Dame’s rushing attack next year. The offensive line replaces four high-quality starters and a 4th round tight end drafted mainly because of his outstanding blocking. A mix of talented young options and veterans with experience remain, but there’s potential for depth to get thin very quickly.

The offensive line is the rare unit often defined by its weakest links instead of the strongest starters. It’s not inherently a problem if true freshmen like Blake Fisher and Rocco Spindler end up starting, but it could a problem if that’s more about the lack of competition than their readiness. The 2017 to 2018 offensive line transition saw massive drop-offs across the board in efficiency and explosiveness. As we know from the team’s record, this wasn’t a fatal blow and represented a drop from an elite run game to around average nationally. But a similar drop-off to an average rushing attack will put a lot of pressure on a new quarterback to drive the offense.

The loss of Ian Book’s legs also looms over this season. With Jack Coan the presumptive favorite to start, there’s one less player for defenses to account for in the run game. If those carries move from QB carries to additional touches for Kyren Williams and Chris Tyree, it’s not necessarily a bad thing. But it increases the emphasis on creating the right kinds of opportunities for the backs to be successful if the blocking in front of them is less dominant.

The upside is that Williams and Tyree are in contention for the best running back duo in college football. Tyree went through some freshman adjustments and had the highest run stuff rate, yet still ended the season at nearly seven yards per carry. Williams was a breakout star and appears to have even more to add in the passing game this coming fall. A more even split of touches between the two will help reduce injury risk, and Tommy Rees should prioritize getting them the ball in space however possible. The question will be how often the tandem can use their speed and elusiveness in the second level of the defense or if they’re constantly required to make defenders miss at the line of scrimmage.

One untapped area in 2020 that offers easy improvement is incorporating receivers in the running game. In 2019 Braden Lenzy chipped in 200 yards on the ground at 15.4 yards per rush, and Lawrence Keys another 45 averaging 7.5. With injuries and different personnel last season, Avery Davis led wideouts with three carries for 57 yards, and Jay Bramblett had more yards rushing than McKinley, Skowronek, and a banged-up Lenzy.

An aspirational yet realistic goal for the Irish in 2021 is a top 30 to 40 rushing attack. A higher ceiling would require a minor miracle worked between Jeff Quinn and Rees, with the young offensive linemen stepping in and dominating alongside Jarrett Patterson. The floor is likely something like 2018, where the Irish finished 72nd in Rushing SP+ struggled with run efficiency.

The most likely avenue for a strong ground attack with this returning personnel is an uptick in explosiveness to offset the anticipated drop-off in run success rates. The team run rate should also fall overall (less early down runs), with Williams and Tyree involved more in the passing game with screens and quick passes that can function like long handoffs. Schematically, Rees will need to look for ways to create space for the backs without a running threat at QB. With the strengths of the offense this season, different rushing approaches could be successful depending on each opponent – the line still may be good enough to “manball” Purdue but not Wisconsin, Cincinnati, or USC.

Great article — loved those graphics about out-of-conference opponents! Based on what you wrote, I think that the solution for 2021 is obvious — give Jay Bramblett the ball more often.

I have no idea what to expect out of the rushing game this year, especially from explosiveness. As noted, losing Book is a big blow there. Obviously the O Line should take a step back. And then this year’s receivers are going to be much less likely to be good downfield blockers.

But could that be offset by more touches for Tyree and Lenzy, as well as a QB/WR group that is more able to stretch the field? Maybe. I’m of the opinion that efficiency is slightly overrated in college football, and that explosiveness is the key to building an elite offense. Hopefully Rees can find a way to generate those big plays, especially in games against stout defenses, where 10 play drives are hard to come by.

you’ll see there’s more to come there as we get to passing offense, but the explosive versus efficient debate is interesting. Bill Connelly’s old work showed that explosiveness is more random and unreliable than efficiency, which makes sense. When you look at the first and second halves of seasons, adjusting for opponents, teams that are good to start with efficiency usually finish that way (and vice versa). Those relying on explosiveness tend to regress to the mean

Looking at 2020 as an example, most of the best offenses essentially do both (explosiveness and efficiency). and there seems to be more successful teams that were efficient but not as explosive (ND, A&M, Iowa State) as opposed to the other combination (Miami, Louisville, UGA, Michigan, K-State hanging out in that area).

I think we have a bit of bias because as a fanbase we’re super thirsty for explosive plays right now. But agree that the efficiency-based offense that works well against less talented teams doesn’t take home the title, I think it’s just hard to scheme/generate explosiveness without just being really good offensively to start. Otherwise you can try to force more explosiveness but probably have to stomach a lot of three and outs.

That makes sense, and I do believe that building an efficient team is probably the best way to consistently beat the teams that have less talent than you. I suppose my concern really is just in the big games. We should be playing a more aggressive style against the opponents that are more talented than us. I understand that could lead to more embarrassing blowouts, but the only way we could have beaten 2020 Alabama would have been to throw the kitchen sink at them, both offensively and defensively.

So thirsty.

Tremble was *ahem* a 3rd round pick.

Also, excellent analysis. This millennial was happy he didn’t have to rely on a Twitter thread.