There’s never been the amount of hype, attention, derision, opinion, exploitation, player rights struggles, sensationalism, and stodgy North American tradition mixed together into one explosive powder keg quite like the teenage years of hockey player Eric Lindros.

You may remember Lindros on the Flyers in the 1990’s, the concussions, or even the draft snub of the Quebec Nordiques but the years that led up to his entrance into pro hockey are some of the wildest and controversial in sports history.

There’s never been quite the level of hype for a player like Lindros. Before him, Wayne Gretzky (1978 WHA signing at 17 years old) and Mario Lemieux (1984 Draft) were bigger stars–certainly in terms of scoring the best ever to play the game–but both missed out on the budding sports radio/ESPN media monster in tandem with the still powerful print media that built up, catered to, and ultimately tore down the Lindros hype beginning in the late 1980’s.

How did we get from teenage hype to grown men dressed as babies in diapers with pacifiers during Lindros’ 4th career NHL game in Quebec City on October 13, 1992?

1) Snub the Soo

Lindros grew up in London, Ontario and moved to Toronto where he played youth hockey for the Toronto Marlies organization. As a 15-year old in the fall of 1988, Lindros shifted to the St. Michael’s Buzzers in the Toronto Metro Junior “B” league where the hype began immediately. Already standing 6’5″ and with a mean streak, he would combine a mixture of scoring and physicality–while playing opponents as much as 5 years older–that quickly captured the attention of the Ontario hockey world.

As a rookie, Lindros totaled 115 points for St. Mike’s in 64 games leading the Buzzers to the league title and OHA Sutherland Cup as the top Junior “B” team in Canada. Those point totals came with a shocking 332 penalty minutes, too.

As the Ontario Hockey League major junior draft approached, Lindros was the clear favorite as the No. 1 pick but this is where the story began to twist.

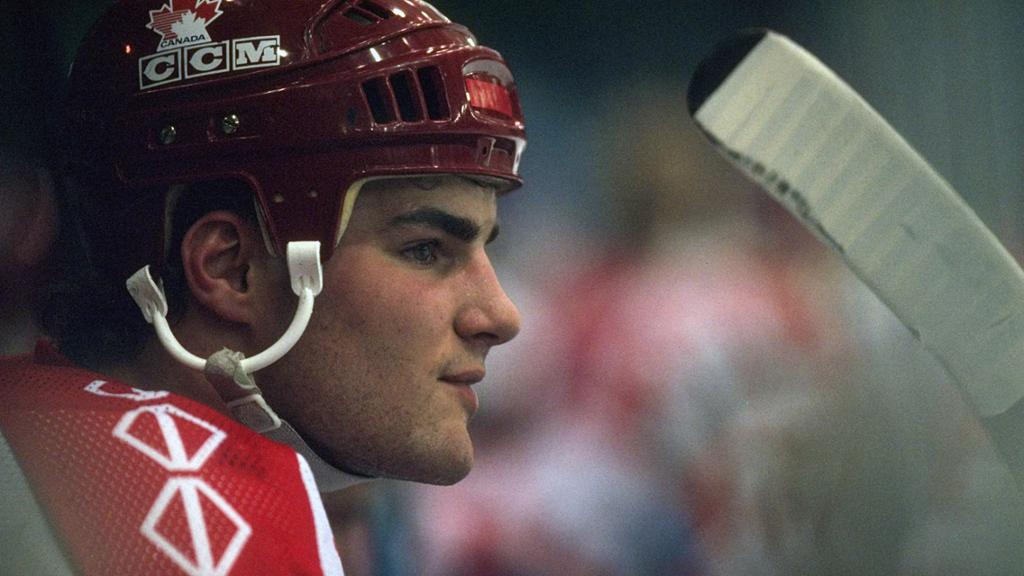

15-year old Lindros with St. Mike’s.

A problem emerged as the Lindros family wanted nothing to do with the Sault St. Marie Greyhounds who owned the 1st pick, were having financial troubles under threat of re-location, and were located 8 hours northwest of Toronto. The family wasn’t interested in the long bus rides of a 66-game season at a team known for skimping on education for their players.

On May 17, 1989 on the day the Soo clinched last place in the OHL (and thus the 1st pick) the team received a $600,000 bid to buy the club. Ten days later, the Soo selected Lindros No. 1 overall.

2) A New Country

Bucking the system and angering the traditional Canadian hockey culture, Lindros refused to report to the Soo, a move not uncommon for hundreds of of other hockey players with other plans but rare for top draft picks and especially the No. 1 selection. Up to this time, the OHL had rules in place where No. 1 draft picks could not be traded for at least one year. So, Lindros sought out other playing options.

He was offered a scholarship to play at the University of Michigan (thank goodness this didn’t happen), looked at New England prep schools, and ultimately decided to billet with a family outside of Detroit and play in the North American Hockey League for the Compuware Ambassadors.

In September 1989, riding the waive of popularity around Lindros, future Hartford Whalers/Carolina Hurricanes owner Peter Karmanos sold his OHL Windsor Spitfires after striking a deal promising to play an exhibition game against the Compuware team with Lindros for the new owners.

As heavy underdogs a tier below, the Compuware team nevertheless pounded Windsor 8-0 in one of the most shocking results in junior hockey history. Lindros scored twice, assisted on 2 other goals, and physically dominated the older OHL team.

In just 14 games with Compuware, Lindros tallied 53 points with an eye-popping 123 penalty minutes.

3) The Lindros Rule

Realizing the Lindros family wasn’t bluffing, the OHL started to scramble without the world’s top pro prospects playing in its league. Well aware of the Lindros hype, Karmanos attempted to buy Sault St. Marie in the winter of 1989 and move them to Detroit. Under enormous pressure, the team was set to be sold to Karmanos for an inflated $1 million ($600,000 was an expected sale price) as the keeper of Lindros’ rights when the city stepped in and raised funds to keep the Greyhounds in Sault St. Marie.

The OHL then created what would be known as “The Lindros Rule” whereby a team had a 10-day window in December to trade their top draft pick if the player was moved in a deal closer to their hometown.

On December 17, 1989 Lindros was packaged in a deal to the Oshawa Generals just outside Toronto for Mike Lenarduzzi, forwards Jason Denomme and Mike DeCoff, a second-round pick in the 1991 OHL draft and fourth-round pick in 1992 OHL draft, plus $80,000 Canadian. A shockingly huge and unprecedented deal for the time.

Lindros would finish up high school in Farmington, Michigan that December, won a gold medal with Canada in the World Juniors, was released by Compuware to join the Oshawa Generals in January 1990 mid-season, and began taking classes at York University in Toronto fulfilling the promise to focus on education.

4) Canadian Hero

The next 18 months pushed the Lindros hype into overdrive. He’d join a veteran Oshawa team that would finish atop the OHL regular season standings, defeat the Kitchener Rangers for the OHL playoff title, then beat Kitchener again for the Memorial Cup as the best team in Canadian major junior hockey. In the playoffs, Lindros led all players with 36 points in 17 games plus 76 penalty minutes.

In the fall of 1990, he’d embark on his only full season with Oshawa eventually leading the league with 149 points in 57 games (winning the scoring title by 21 points in 8 fewer games played than the 2nd place finisher) still with an enforcer-level 189 penalty minutes. Although the Generals fells to the Soo (irony, right?) in the OHL Finals, Lindros dazzled in the 1990-91 winter World Junior Championships leading Canada to gold with 17 points in 6 games.

Attention then turned to the upcoming 1991 NHL Draft where the Quebec Nordiques clinched last place in the league by 11 points and would be making their 3rd straight No. 1 overall pick.

5) Canadian Villain

Nine days before the NHL Draft, Bonnie Lindros indicated in an interview that her son would not play for Quebec. Canada about burned up with indignation! For the traditionalist structure world of hockey, the upcoming star player was pulling the same stunt in the NHL as he did in the OHL.

For critics the reasoning was simple, Lindros had helicopter parents (there was no shortage of sexism against his mom at the time), they were selfish, and the family didn’t want to learn French. While there may be truth to these statements, Lindros did end up marrying a French woman and it was rumored that an inappropriate comment* made in French from Nordiques owner Marcel Aubut to Bonnie Lindros (who spoke French) essentially sealed a fractured relationship between the parties.

With hindsight and more modern sensibilities it’s easier to understand the Lindros decision. Quebec was by far the smallest market in the NHL, had been struggling financially for years, had no history of winning, the team was perpetually on shaky foundation with the threat of moving, and in 1991 the Canadian dollar was tanking.

On June 22, 1991 the Nordiques selected Lindros No. 1 overall anyway.

*To this day, Lindros remains steadfast that the decision was because of Aubut. Many years later, Aubut would later resign from his job with Hockey Canada after several allegations of sexual impropriety.

6) The Trade

True to his word, Lindros refused to sign with Quebec and would publish an autobiography about his life several months later. He would make the Canada Cup team that summer as the only non-NHL player then split his time between Oshawa (31 points in 13 games) and the Canadian National Team participating both at the World Juniors again and for the Albertville 1992 Winter Olympics.

Lindros’ autobiography published in October 1991.

Quebec finished with the 2nd worse record in the 1991-92 NHL season, only ahead of the expansion San Jose Sharks. On June 10, 1992 just a week past the end of the season, reports broke that the Nordiques had dealt Lindros to the New York Rangers AND Philadelphia Flyers.

Ten days later, an arbitrator ruled in favor of the Flyers.

The bounty sent to Quebec became the most famous trade in league history with the Nordiques receiving Mike Ricci, Peter Forsberg, Steve Duchesne, Kerry Huffman, Ron Hextall and future considerations (eventually Chris Simon) plus the Flyers’ first-round choice in the 1993 entry draft (eventually Jocelyn Thibault) and 1994 entry draft (later traded to Toronto and then Washington, who selected Nolan Baumgartner) plus $15 million in American dollars.

7) The Move

The bounty sent to Quebec helped the Nordiques on the ice where they shot up to the 4th most points in the league for 1992-93 although a 1st round playoff exit to provincial rival Montreal stung deeply. Lindros signed a monumental 5-year $22 million deal with the Flyers and finally began his NHL career.

Two years later, the end was finally near for the Nordiques. Following the end of the 1994-95 season, Quebec finished 1st in the Eastern Conference in points but again fell in the first round of the playoffs, this time to the New York Rangers. Playing a lockout-shortened season brought on by rising player salaries and no salary cap (Lindros’ rookie deal effectively made him the game’s highest-paid player) the summer of 1995 saw Lindros named league MVP, the second youngest ever in league history behind Wayne Gretzky.

Aubut refused a $50 million bailout of the Nordiques from the government of Quebec without financing a new arena and turned away suitors (including our old friend Peter Karmanos still looking for a NHL team) offering up to $60 million for the franchise. Just 12 days after their final game and playoff exit to the Rangers, Aubut accepted a $75 million deal from COMSAT (then the owners of the NBA Nuggets) who would move the team to Denver to be re-named the Colorado Avalanche.

The Avalanche would win the Stanley Cup in 1995-96 in their first season after leaving Quebec City.

***

Drama would continue to follow Lindros but once in the NHL his struggles revolved mostly around injuries. Through his first 5 seasons he missed 79 games with a bevy of ailments. Between March 7, 1998 and May 26, 2000 he suffered 6 documented concussions and never played for the Flyers after the last devastating hit in game 7 of the Eastern Conference Finals from Scott Stevens.

Lindros was the 5th fastest player ever to score 500 points (trailing Wayne Gretzky, Mario Lemieux, Peter Stasny, and Mike Bossy) and did so faster (352 games) than current stars Sidney Crosby and Connor McDavid (both 369 games) who are also in the Top 10 all-time. While with Philadelphia, Lindros’ 1.36 points per game ranked him tops in organization history by a wide margin and would be 6th all-time in NHL history today. After 201 points in 274 games across 5 injury-filled seasons with the Rangers, Leafs, and Stars that scoring average dropped down to 18th all-time today.

You can quibble that Eric Lindros didn’t ‘save’ Windsor, Sault St. Marie, or the Nordiques but his career was a fascinating tale of the tug of war between player and franchise, the struggle of team financial stability in the face of burgeoning players’ rights and increasing salaries, a family and outspoken mother challenging decades of blue-collar culture, plus a sordid story of how sports teams are awarded bargaining chips for losing games and how someone still just a teenager can have such a ripple effect for so many franchises without ever playing for a team.

My favorite athlete of all-time. Some day I’ll get this biography done and a book deal signed.

Other than his brief stint with a curly-ish semi-mullet, he has to be one of the most generic looking white guys of all time. Surprising voice for such a giant human, too.

Great early 90’s hockey hair.

NHL ’99 for N64 made me a Lindros fan. What a squad. Lindros / LeClair / Brind’Amour (I had to move him to RW) / Desjardins / Some other defenceman / Hextall was an absolute unit of a first team.

(I also repped the Steelers in Madden ’64, despite not being from/having any allegiance to Pennsylvania.)

Some other defenseman sums up that era for the Flyers, sadly.

Hextall had a .888 save percentage in 1999-2000 which would’ve put him 81st this past year in the NHL. The league has changed so, so much.

Hard to believe there were 80 other qualified goalies to make up that statistic.

Great article. Lindros took the extra step than Lemieux, who was unhappy the Penguins didn’t agree to contract terms with him prior to the ’84 draft. And while he attended the draft he didn’t go on stage and shake hands or put on a Penguin jersey. Awkward. Worked out since they eventually ponied up for him and all was forgotten.

I could be slightly off, but I think Lemieux wanted to come into the league as the 3rd highest player (behind Gretzky and Messier), and if it wasn’t that it was close, at least top 5 salary. That’s pretty similar in spirit to Lindros’ contractual demands, though as detailed above they decided Quebec was always a no-go for non-financial reasons.

Pretty crazy in this day and age to think about now that all rookie contracts have long since been collectively bargained away into standard slotted amounts (by players associations/unions that rookies don’t belong to!) which standardizes and fairly heavily depresses what rookies can earn on their first contracts.

Wild how in NHL players like Ovechkin, Crosby and McDavid have won MVP’s early in their career with about $1 million in base salary (and about $4 million total with incentives) where other veterans are earning more than double that total compensation.

The Lemieux situation on draft day is one of those stories that kind of gets buried these days but that could’ve been absolutely massive for the sport if it got uglier.

I always wonder if there were people in Pittsburgh who hated Mario at the time for acting that way and it’s funny that they can look back and see he brought 2 Cups and would become part-owner.

“Winning is a great deoderant.” – John Madden – John Gruden – Michael Scott

From talking to uncles and older relatives alive at that time, there was a little “oh this is an entitled athlete” but all the hype was Lemieux was an unreal player who could save the franchise. And most people in Pittsburgh cared nothing for hockey and the team was barely hanging on, and in context this was right after the Super Steelers and We are a Family Pirates eras, so the Penguins were very much considered a joke and didn’t have a lot of support.

So I think, at least in my family, the lasting memory was “this team better legitimize themselves and actually do something for once” more than blowback on Lemieux for his stance.

And then his first shift he burned Ray Bourque and scored on a breakaway so everything was super, super quickly forgotten.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sBbp3evqoPs

Lemieux was outrageous. Tall, could skate so well, a 47-foot stick with hands of butter.